Driving Improvements in Established Programs: A CWS Summit 2015 Post-Roundtable Discussion

Leslie Marsh, SPHR

Vice President, Channel Partnerships at HireTalent

December 2015

I. Introduction

During our roundtable discussions at CWS Summit 2015 (Fig. 1), we discussed the process of identifying areas for continual process improvement and the enabling of these areas of opportunity within Managed Service Provider (MSP) programs. Simply put, ensuring we “get better all the time.”

Fig. 1

As the last ten years have proven, the MSP model is here to stay. In looking to the future of the MSP, a glance back to industry and academia can provide us with a grounded perspective on how organizations can continue to evolve in practice and process to deliver best-in-class results.

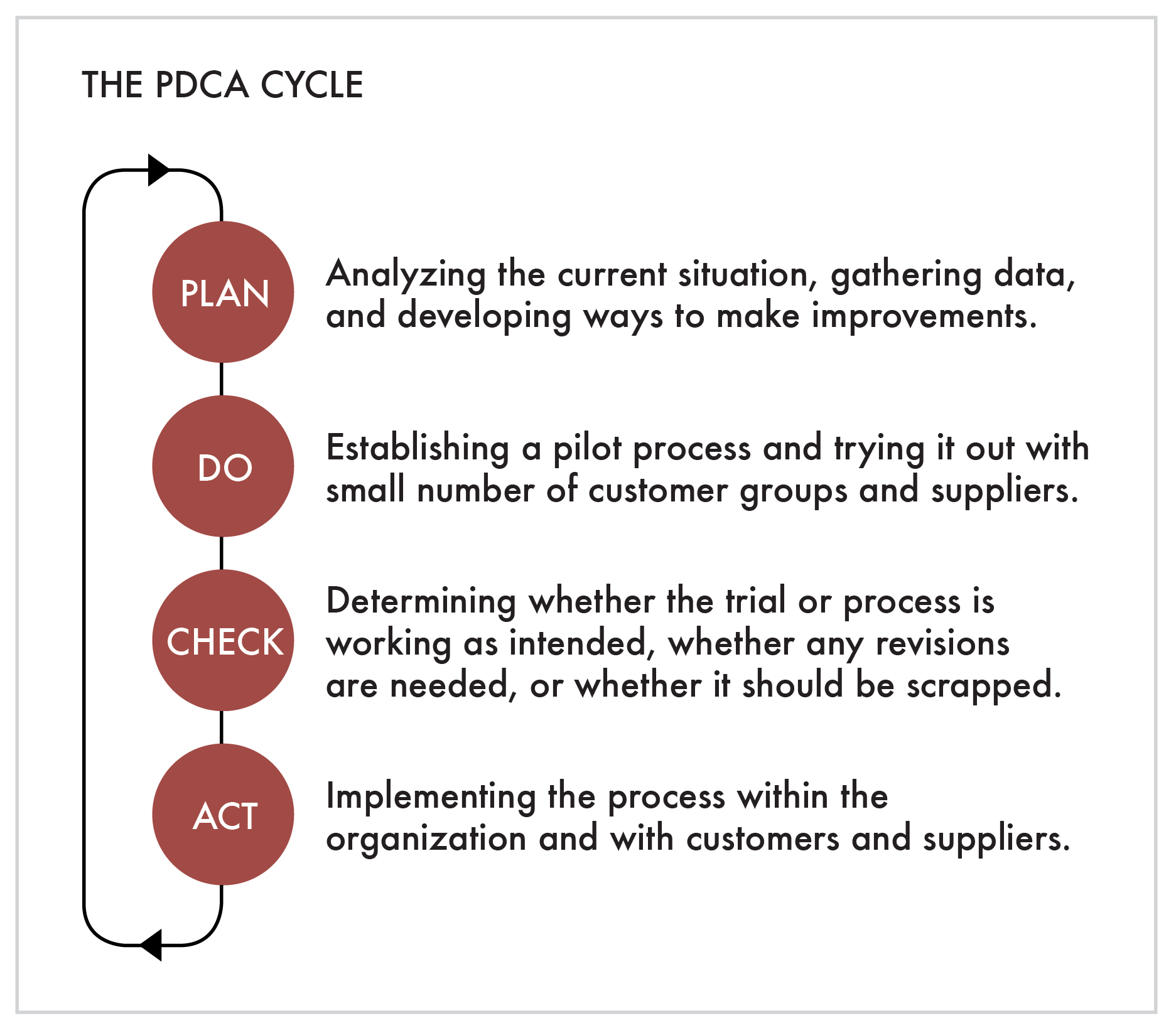

W. Edwards Deming, the famous “quality guru,” saw continuous process improvement as part of the system whereby feedback from the process and customer are evaluated against organizational goals. Deming offered a “PDCA Cycle” (an acronym of “Plan, Do, Check and Action”) repeated over time as a method for ensuring continuous learning and improvements in a function, product, or process.

Later, Deming’s findings inspired the well-known Six Sigma concepts for continual process improvement, as illustrated below (Fig.2). It is common for the “Define” phase to be utilized during the launch of MSP programs and for the “Measure” and “Analyze” phases to be utilized in quarterly and annual business reviews. However, not to be less utilized are the latter “Improve” and “Control” phases of the cycle which inspire continual process improvement through pilot programs and performance measurement. These latter phases create opportunities for mature MSPs to bring to life continuous process improvement strategies as well as sustain program control through the establishment of proprietary rights policies for the contingent workforce.

With our recent discussion and these quality concepts in mind, HireTalent presents industry practices and strategies that can be assessed and utilized to meet evolving performance standards.

II. Value Adds & Challenges of the Managed Service Provider Program

In general, the key returns orbiting a MSP are visibility, compliance, and cost control of the contingent workforce. Whether through in-house or off-the-shelf systems, large and complex organizations with diverse contingent workforce populations are utilizing Vendor Management Systems (VMS) to obtain the rich data of centralized invoicing, financial oversight, and analytics.

VMS provide data to program management teams who then in turn develop the analytics around what is working and what “still needs work” within programs. However, some industry leaders argue that MSP programs are only answering the “how” and not the “why” of a program’s success. A deeper data analysis will produce and enable new strategy fueled by the “why.”

Another critical value add of an MSP is the ability of a program to streamline recruitment, on-boarding, and off-boarding processes – often with global capabilities. Most VMS tools have integration features compatible with proprietary Human Resources and Security tools to ensure compliance with background screening requirements, and control facility and IT access rights. Alas with every rule, there is an exception, and in the world of the MSP this axiom manifests itself as process and rate card exceptions. The reality of rate card exceptions (also known as fills selected outside of the program) is that they negate any true cost savings the MSP bears and erode program utilization. The byproduct of process exceptions is that they reduce the amount of security and control over access and proprietary rights the program establishes. All of these byproducts ultimately underline the program.

We should also consider that our current economic conditions have created career opportunities for top talent and in turn, have created competition for talent. Strong vendor partnerships – those vendors tied into passive talent pools and adept at creative recruiting strategies – are increasingly being recognized as key to the talent supply chain. Research from Staffing Industry Analysts in 2015 find worker quality is overwhelmingly the number one selection criteria for choosing staffing partners.

In this vein, vendor assessment, optimization, and vendor entry/exit are high on the list of program benefits. It’s important to note that a common struggle among MSPs (including mature programs) is the level of stakeholder participation by Human Resources and Procurement colleagues. It is critical that program leadership, particularly in terms of vendor relationship management, is socialized within an organization with a unified message and strategy or the program will continue to encounter rate card and process exception requests.

Finally, the industry is finding that top talent is increasingly choosing to act as a free agent in the form of independent contractors, freelance business owners, and temporary workers. Risk mitigation around employment classification has been prevalent for years and continues to remain critical, particularly as mature MSPs begin to absorb Statement of Work (SOW) resources into their programs and VMS tools.

III. Strategies: Ensuring Ongoing Program Improvement

Let’s take a closer look at some of the factors contributing to successful program evolution. Perhaps the most critical factor to establishing and maintaining a best-in-class program with organizational buy-in is active participation and sponsorship of the program by Executive leadership, Procurement, Human Resources, and Finance stakeholders. Establishing a regular communications cadence driven by these internal partners ensures a clear message of support for the program. In this way, contingent workforce strategy is socialized within the organization and recognition of the value and contributions of the contingent workforce is provided. In turn, this messaging empowers program management teams with the support of business leadership and aligns them to the strategic goals of the stakeholders.

In order to preserve control of the entry/exit of the contingent workforce, Programs must also develop, define, and socialize a strategic plan for management of proprietary rights granted to the consultant population. For example, organizations that absorb a SOW population within a centralized program often struggle with identifying which consultants should be granted facilities access if some portion of the project is to be completed off site. Should the policy grant all SOW consultants full IT and facilities access or are there significant risks inherent in that approach? Each organization will have a different answer to this question and definition of policy is essential to ensure that the entire contingent population is enabled with the tools necessary to contribute to successful completion of their responsibilities.

A key component of the “Plan” / “Define” stages established by Deming and Six Sigma concepts is often overlooked: the establishment of a Mission, Vision, and Value statements for the MSP. How effectively can the present state (Mission), future state (Vision), and strategy (Value) be defined and achieved without dedicating energies to creating these definitions? One can argue not well. These statements immediately establish clarity of culture, strategy, and preferred values for stakeholders and vendors. They will organically drive process and policy into a vendor’s recruitment approach and influence candidate experience. Keep in mind that these statements should also be “Checked” and “Improved” just as process and policy. Given the dynamic business climate organizations operate within, the program needs to remain flexible.

The measurement and optimization of vendor partners paired with the introduction of new partners are also keys to program evolution in terms of keeping competitive fires burning in the vendor community. In the case of an external/third party MSP provider, it is critical that vendor management exercises are completed jointly between the program management team and client stakeholders.

The knee jerk response of stakeholders and program management teams tends to eschew the addition of new vendors. Undoubtedly, it can be overwhelming to an organization to understand the “why” around vendor relationship management. Therefore, the default response to vendors inquiring about joining the program becomes: “we are not adding new vendors at this time.” This approach coupled with a lack of action around “Improving” an environment with a significant level of underperformance by optimizing existing vendors, creates missed strategic vendor partnerships. All possible avenues of improving existing vendor partnerships should be explored to encourage improved performance and program compliance. Probation periods and optimization efforts must be actioned (“Improved”) in the case of vendor partnerships that are misaligned to program strategy and/or non-compliant in terms of process and best practice. The addition of new vendors should also be recognized in that this practice allows for organizations to integrate new recruiting talent with a hunger to prove their merit.

In terms of new vendor selection, data analysis allows for the identification of skillsets and geographic areas with a lighter level of vendor engagement. There are new vendors specializing in deep, niche recruiting as well as those specializing in challenging geographies that the large national players perceive as low ROI, paying little attention to them. In terms of vendor management, MSPs may look to create a niche vendor community or tier to offer new vendors an opportunity for program success in a pilot environment, and closely monitor their performance during this trial period.

How can MSPs attract these newer, entrepreneurial vendor organizations?

Offer a significant opportunity

Ensure attraction and interest in the MSP with a) a realistic volume of Job Requisitions, and b) by providing Job Requisitions in a reasonable timeframe; in other words, distributing Job Requisitions to new vendors prior to or at the same time that active vendors receive it. Then, measure performance during the pilot period and if the new vendors are successful, grow the relationships with a greater volume of Job Requisitions with a larger skill set and/or geography. Ensure that the best recruiting vendors are incented to participate in the MSP “pay to play” model.

Set realistic expectations

Standard terms and conditions may not incent niche vendors to accept an opportunity to join an MSP program. Allow for customization of insurance requirements and/or payment terms whenever possible to encourage new vendor participation. What is acceptable to a large, national vendor partner is not necessarily an attractive opportunity for a start-up organization.

Open up the lines of communication

The kind of vendor that organizations and program management teams value are vendors that act as true partners. Seek to establish partnership with vendors whose teams are closely aligned and in tune with the information, processes, and culture the MSP is establishing versus those that attempt to bypass the program management teams in hopes of circumventing their competition. With that said, attraction is a two-way street. In general, vendors seek programs with accessible and available teams. For example:

Daily and operational activities: Ensure that the program management teams are completing the basics such as answering their phone and email with inquiries about Job Requisitions, resume submittals, and timecard approvals. Educate managers of Job Requisitions on how to respond to sales calls by being open and receptive, and then redirecting the vendors back to the MSP. Does the organization have a centralized and up to date contact list for the program management team?

Formalized events and communications: Establish a cadence for annual vendor forums with Q&A sessions. Vendors highly value the opportunity to make an in-person introduction with the program management teams, HR, and procurement stakeholders. Develop an annual business review message that is general enough to be shared with an external vendor community, yet meaningful enough to allow vendor teams to align themselves with business forecasts.

Programs must also ensure that the data output of sophisticated VMS is being applied robustly in continuous process improvement strategies. Given the program management teams’ daily operational oversight of the contingent workforce platform, they are best positioned to benchmark overall program and vendor performance against industry standards.

IV. Conclusion

We encourage our colleagues to stay close with and utilize the basic principles of Deming’s continuous process improvement and Six Sigma concepts: Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, and Control. Regularly dedicate efforts to the piloting and measurement of new strategies, and engage new vendor partners. Keep in mind that the strategies that work well today may be ineffective tomorrow!

Our recent discussion and the proposals set forth in this paper offer stakeholders strategies to get in front of the changing world of the MSP rather than follow the change. Ultimately, each organization operates as an independent ecosystem and strategies must be customized to fit.

Contingent workforce management is an exciting space that offers a dynamic and challenging environment for program teams, Procurement, and Human Resources stakeholders to solve the daily challenges of strategically attracting, retaining, and managing client, vendor, and consultant expectations.

For additional conversation around any of these topics, please reach out to Leslie Marsh at leslie@hiretalent.com | 914.620.7972. We are excited to debut this White Paper as the first in a series identifying challenges and offering market solutions within the industry.

“Learn from yesterday, live for today, and hope for tomorrow. The important thing is to not stop questioning…”

– Albert Einstein

V. Appendix: CWS Roundtable Discussion Notes

In terms of program sponsorship, Human Resources/Talent (HR) and Finance are key stakeholders whose active participation and labor expertise are critical to the success of the program. HR & Finance’s partnership with the supply chain will assist in setting process and governance of the program. In terms of program operations, there must be one established point of contact i.e. a Program Manager who orchestrates key stakeholders and influences change management.

Many of the roundtable participants have completed or are in the process of absorbing Statement of Work (SOW) spend and headcount into MSPs and VMS tools. Shared challenges in doing so generally revolved around lack of participation by Finance, IT, HR and Procurement stakeholders.

In terms of managing exception requests, the general opinion of participants was that a firm adherence to defined program processes and policies (on behalf of all stakeholders) reduce and ultimately eradicate exceptions in on boarding and invoicing requests. The trend is for all headcount to run through the program.

There were questions around methodology used in how to properly define SOW vs. Staff Augmentation and how to clearly communicate process for on boarding to internal clients. Participants recommended having both methodology and process housed on internal sites that allow for clear solutions to all program requests.

In addition, there was some discussion around which VMS tools are most successful in supporting a SOW component of the program and the groups were in agreement that all the major VMS tools were comparable. Also on a positive note, there were several participants that confirmed that their organization’s use of VMS tools for SOW bidding is regularly occurring. However, there was some concern around the validity of the data produced by the VMS tools.

Another challenge for Program Managers is making sense of the discrepancies across data that the various systems being used by Legal, HR, and Procurement as compared to the data their VMS tools provide. There is a need for a centralized system that integrates multiple systems into the VMS tool and ownership of who is the record keeper for budget and spend.

Ultimately, poor headcount visibility and compliance risk are the results of a lack of clear SOW and staff augmentation populations. VMS tools are key for financial oversight however “garbage in, garbage out,” so it is critical to ensure resources are properly classified prior to being absorbed in the program. Whether the program is an Internally Managed Program (IMP) or goes through a third party provider, audit and pay/bill rate visibility is key to creating control and cost containment.

VI. References

Nameer. (2009, February 25) “Deming Cycle: The Wheel of Continuous Improvement” {Web Log Post} Retrieved from https://totalqualitymanagement.wordpress.com/2009/02/25/deming-cycle-the-wheel-of-continuous-improvement/

Wloczewski, Ceil. (2013, February 19) “Three Things You Can’t Do Without – Mission, Vision, and Values Statements” {Web Log Post} Retrieved from http://www.cellaconsulting.com/blog/three-things-you-cant-do-without-mission-vision-and-values-statements/

Mahaffy, Dr Samuel (2014, May 13) “The Danger of Mission Statements” {LinkedIn Post} https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/20140513193936-10474781-the-danger-of-mission-statements